I talked briefly about subnetting IPV4 in this other post https://itlessonslearn.com/2023/03/01/a-brief-introduction-to-network-ipv4-addresses/. This post focuses on how to subnet IPV4 and more or less assumes the reader has not do subnetting before. This will be a bit of a retread. In the useful links below, I’ve included a link to an online calculator that can do this for you automatically if you want to take easier route. The first step in understanding subnetting is that binary machines view all data as a series of 1’s or TRUE and 0’s FALSE. A bit is the smallest unit of data storage for computers and our current machines store many bits. Binary machines manipulate bits and do something based on the results. The binary number system functions as powers of 2 and generally will start at the right most bit and work its way down. For example, 245 as binary looks like 11110101 and the right most binary which happens to be set is equal to 1 in decimal. The left most bit is also 1 but its place value in decimal is 128. Binary is a zero-based number system. So, in a binary, the number places 1-8 are actually 0-7 and so on.

In the tables below, there is a few collections of what happens to bits when ran thru the relevant bitwise operation. For readability, the set bits (which are equal to 1) are listed as true and the cleared bits (which are equal to 0) are listed as false.

| AND Operation (All bits must be true to set output bit to true) | ||

| TRUE | TRUE | TRUE |

| FALSE | TRUE | FALSE |

| FALSE | FALSE | FALSE |

| TRUE | FALSE | FALSE |

| OR Operation (Only one bit out of any in a series of bits needs to be true to set output true) | ||

| TRUE | TRUE | TRUE |

| FALSE | TRUE | TRUE |

| FALSE | FALSE | FALSE |

| TRUE | FALSE | TRUE |

| XOR Operation (Either bit BUT NOT BOTH need to be true to set output as true) | ||

| TRUE | TRUE | FALSE |

| FALSE | TRUE | TRUE |

| FALSE | FALSE | FALSE |

| TRUE | FALSE | TRUE |

| NOT Operation (Flip input bit) | |

| TRUE | FALSE |

| FALSE | TRUE |

How a left most significant byte (8 bits) looks like.

| 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 0 or 1 | 0 or 1 | 0 or 1 | 0 or 1 | 0 or 1 | 0 or 1 | 0 or 1 | 0 or 1 |

Going between binary and decimal is as easy as taking the power of 2 out a number. I’ll break down the number 204 to binary as an example. We already know that it can be stored in 8 bits.

| 204 |

| -128 |

| 76 |

Don’t forgot to set bit 7 to 1.

| 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 |

Next, let’s half our 128 to 64 (bit 6) and see if it’s not too large to take out 76.

| 76 |

| -64 |

| 12 |

It’s not. Yay!

Don’t forgot to set bit 6 to 1.

| 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 |

Let’s keep going. 32 is too large. Half of 32 is 16 and that’s still too large for our needs. This means we set bits 5 and 4 to 0 also.

| 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Next, let’s see if 8 can be taking out of 12. It can and leaves us with 4 which happens to be a power of 2. Don’t forget to set bit 4 to true.

| 12 |

| -8 |

| 4 |

| 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

With 4 being all that’s left, we can just set bit 3 to true while setting bits 2 and 1 to false. It would look like this table below.

| 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

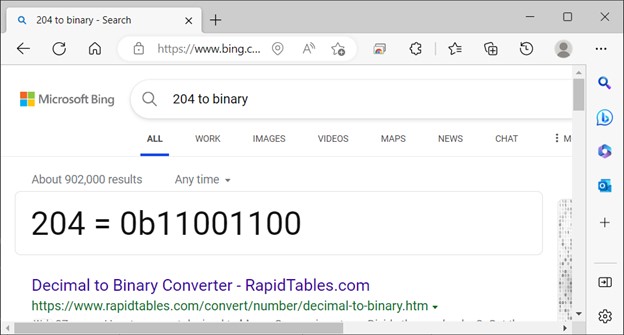

One quick plug into Bing and we got a screenshot of the binary value for 204. Note that the 0b at the beginning is being used to indicate that the 11001100 number is binary rather than decimal.

There are tools to do things like this but said tools may not be allowed if one is taking a proctored test. The useful links include the tool used for the above screenshot. For that reason, it’s useful to know how to do it manually if the need arises.

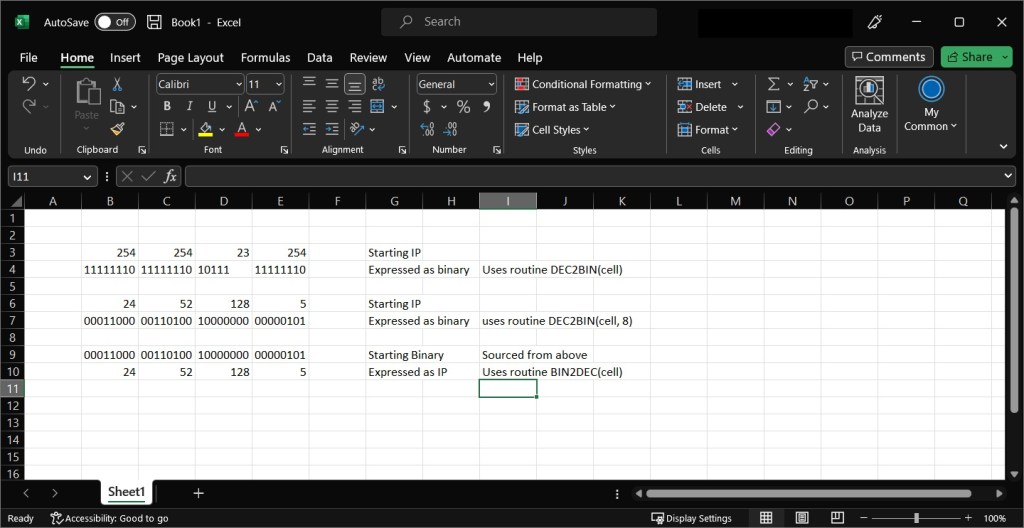

One thing that can be useful is a spreadsheet application such as Excel or Apache OpenOffice – Official Download if Excel is unavailable. The function in Excell is called ‘DEC2BIN’ and it takes a decimal number either from a cell or a hardcoded specific decimal number and outputs the equivalent in binary. One will need to be a little careful in mentally filling out blanks or just specify how many places that are desired in the output number. The table below shows some simple Excel formulates to get started.

| =DEC2BIN(A2) | Convert the number in cell A2 to binary |

| =DEC2BIN(25,8) | Convert 25 to binary and used 8 numerical places to store it. |

| =BIN2DEC(cell) | Convert the passed number expressed in binary to decimal. |

This concludes the post. My plan for posting is once a week on Mondays but that did not happen this week. My apologies. Next post will break down the IPv4 Addressing format, what’s a network mask and why subnetting is useful in large networks. If I can get it to work, I’ll upload a Packet Tracer set do demonstrate the difference between a network that’s subnetted and one that’s not.

Useful links:

Decimal to Binary Converter (rapidtables.com) – use an online tool.

Cisco Packet Tracer – Networking Simulation Tool (netacad.com) – get starting learning about networks for FREE.

IP Subnet Calculator – use an existing tool.

Leave a comment